The Core Knowledge HypothesisĬore knowledge theory articulates a cognitive hypothesis regarding the origins of knowledge (for reviews, see Spelke, 1994 Carey and Spelke, 1996 Spelke, 2000 Spelke and Kinzler, 2007 Carey, 2009). My discussion begins with a brief summary of this hypothesis, followed by a discussion of Everett’s methodological concerns. To appreciate Everett’s (2016b) critique of nativist theories of language, it is important to consider it within his broader critique of cognitive nativism, specifically, the core knowledge hypothesis. While my reply focuses mostly on the arguments in Everett (2016a), the broader context is set in reference to his upcoming book, Dark Matter of the Mind, of which Everett (2016b) is an excerpt. Everett’s remaining arguments against The Phonological Mind thesis are discussed in the final section.

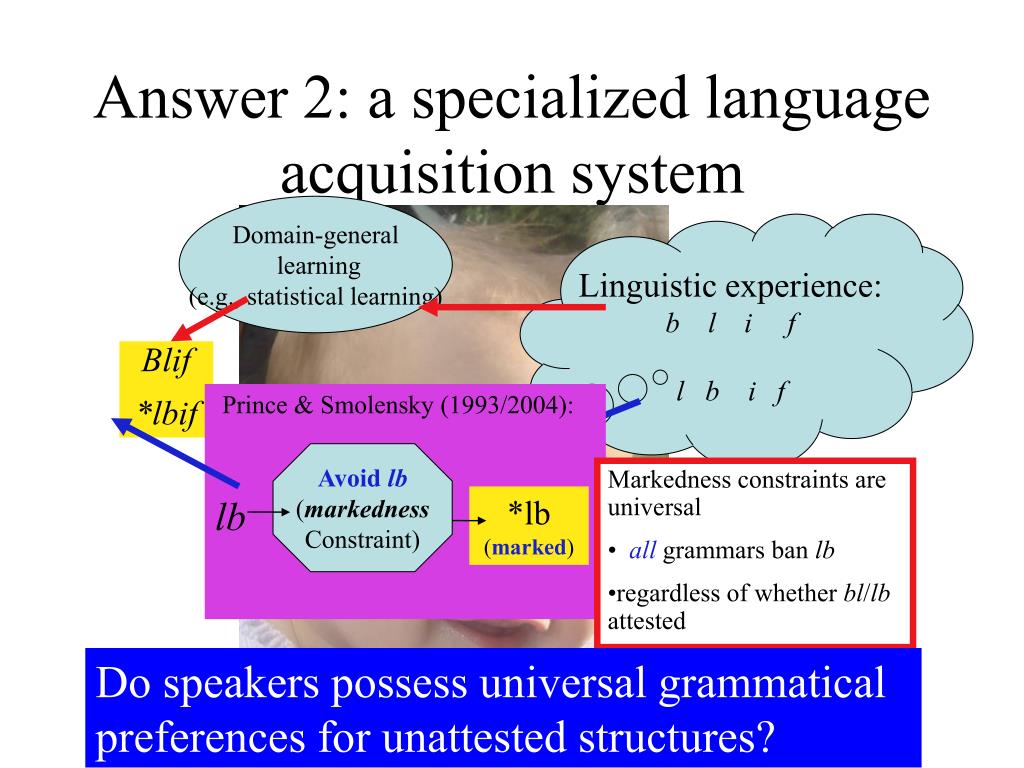

Having established some ground rules for testing the core knowledge hypothesis, I proceed to consider the evidence for innate phonological constraints by evaluating the empirical evidence for UG in a particular case study-the restrictions on syllable structure. I first consider Everett’s broader critique of cognitive nativism and address his logical and methodological concerns about the falsification of nativist claims and their congruency with genetic and evolutionary evidence. But Everett’s superficial reading of the scientific literature and his incendiary rhetoric do not challenge this hypothesis. Whether Universal Grammar exists remains unknown-a fact that (contrary to Everett’s claims) I openly acknowledge. Similarly, in his attack on The Phonological Mind’s thesis, Everett ignores most of the relevant experimental evidence, he systematically misrepresents my claims, and his characterization of my approach is disingenuous. Everett’s broader objections to cognitive nativism are rooted in an erroneous conflation of explanations at the cognitive and biological levels, an implausible view of the links between the cognitive phenotype and the genotype, and a disregard for a large experimental literature that counters his assertions. I believe Everett’s concerns are unfounded. The Phonological Mind thesis, then, exemplifies what has gone so wrong in cognitive nativism. Rather, it is an entire class of nativist accounts of cognition, specifically, the “core knowledge” hypothesis, that is bankrupt. The problem, according to Everett, is not limited to this particular theory of phonology, or even language. It defends a formal linguistic account that is blatantly false, its experimental support is confounded by trivial “perceptual” factors, and its biological bases are at best tenuous. The Phonological Mind thesis ( Berent, 2013a, b), according to Everett (2016b), is plainly silly. Whether Universal Grammar exists remains unknown, but Everett’s arguments hardly undermine the viability of this hypothesis. A detailed analysis of one case study, the syllable hierarchy, presents a specific demonstration that people have knowledge of putatively universal principles that are unattested in their language and these principles are most likely linguistic in nature.

#SONORITY PLATEAUS FULL#

Contrary to Everett’s logical challenges, here I show that the UG hypothesis is readily falsifiable, that universality is not inconsistent with innateness (Everett’s arguments to the contrary are rooted in a basic confusion of the UG phenotype and the genotype), and that its empirical evaluation does not require a full evolutionary account of language. Most of Everett’s concerns are directed toward the hypothesis that the phonological grammar is constrained by universal grammatical (UG) principles. Phonology and Reading Laboratory, Department of Psychology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USAĮverett (2016b) criticizes The Phonological Mind thesis ( Berent, 2013a, b) on logical, methodological and empirical grounds.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)